Rediscovering the Charm of Manual Photography

Rediscovering the Charm of Manual Photography

Rediscovering the Charm of Manual Photography: Using Vintage Lenses on Modern Mirrorless Cameras

The Why Behind the Try

I never thought I’d be tempted to stray from my modern autofocus lenses, even though I was fully aware of the quality of some older lenses having used Takumar and Pentax glass back in the late 1970s and 1980s. But nostalgia only goes so far when you take your photography seriously, and I wasn’t about to trade lightning-fast autofocus, in-body stabilisation and weather-sealing for the sake of a memory, or so I thought.

A close friend (Wes, you know who you are), whose insight and opinions I trust entirely, started showing me images from a vintage Takumar 50mm F/1.4 mounted on a Sony A7 IV. The colours, the bokeh, the feel; it was different. Not clinically perfect, but undeniably beautiful. Intrigued, but still somewhat skeptical I turned to online opinions and reviews, eventually I caved.

I dusted off an old Pentax SMC 55mm F/1.8 that I had boxed away years ago, grabbed a $40 adapter plate (K&F Concepts) from eBay, and started shooting with it on my Sony A7RIV and Sony A7 (720nm Infrared Converted). That’s where this little experiment began.

Liking what I saw, I decided to expand the experiment and pad out my vintage lens collection with a selection of wide to standard prime lenses. Three Takumars, the SMC SMC 24mm F3.5, SMC 28mm F3.5, and SMC 50mm F1.4, as well as a HELIOS 44M-4 58mm F2.

My little family of vintage lenses

First Impressions and Build Quality

First things first—vintage lenses are retro in all the right ways. They don’t feel like consumer electronics. They feel like crafted tools. They were made to last.

All the lenses mentioned here are made almost entirely of metal and glass, no plastic. They are compact, reassuringly weighty for their size, and exude a kind of mechanical confidence that a lot of modern lenses just don’t offer anymore.

The HELIOS is somewhat the odd one out in this new collection of vintage glass. Purchased mainly as a swirly bokeh beast, I was well aware of the variable nature of this lens’s quality control. Coming out of the Valdai plant, my version seemed to exhibit some of the quirks these Soviet lenses are known for, looseness and play in both the camera mount and front lens housing, but the glass was clean, and the aperture blades free from oil residue. You could have used the lens as a maraca it rattled so much. While potentially a problem for videographers, this did not detract from the still photos taken with it. Nevertheless the rattle annoyed me, so I purchased a lens wrench and discovered that all the looseness and rattles were caused by loose screws. I suspect the lens had been disassembled for cleaning and not sufficiently tightened while being put back together.

The focus rings on all lenses are buttery smooth with just the right amount of resistance, and the aperture rings clicks firmly into place, no mushy or loose stops.

Holding them was enough to remind me why photographers get a bit romantic about old gear.

These lenses are compact, even attached to the adapter, they are amongst the shortest (and lightest) lenses in my collection. They feel nicely balanced in hand, certainly not out of place on either of my Sony cameras.

Features and Specs That Matter

Let’s be real, vintage lenses don’t have features, at least not in the modern sense. No autofocus. No image stabilisation. No weather sealing. No electronic connection at all.

But what they do have is compatibility. With a simple adapter ring (K-to-E and M42-to-E mount in my case), they slotted onto both Sonys like they belonged there. I had to enable “shoot without lens” on both cameras, and from there it was manual everything: aperture, focus, and exposure.

The good news? It made me slow down. And that is perhaps the crucial point to this experiment, using the manual lenses has forced me to have a more contemplative approach to photography.

Field Use & Performance

I took the lenses to my local beaches and bush walks, getting a feel for each of them and to help me identify and understand any idiosyncracies. I wasn’t particularly shooting with any artistic intent, but, nevertheless, managed to capture some photos I was quite happy with.

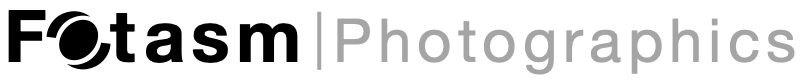

Sony A7RIV with SMC Takumar 50mm F1.4 – 1/100th at F8

Sony A7RIV with SMC Pentax 55mm F1.8 – 1/60th at F8

Sony A7RIV with SMC Takumar 28mm F3.5 – 1/60th at F8

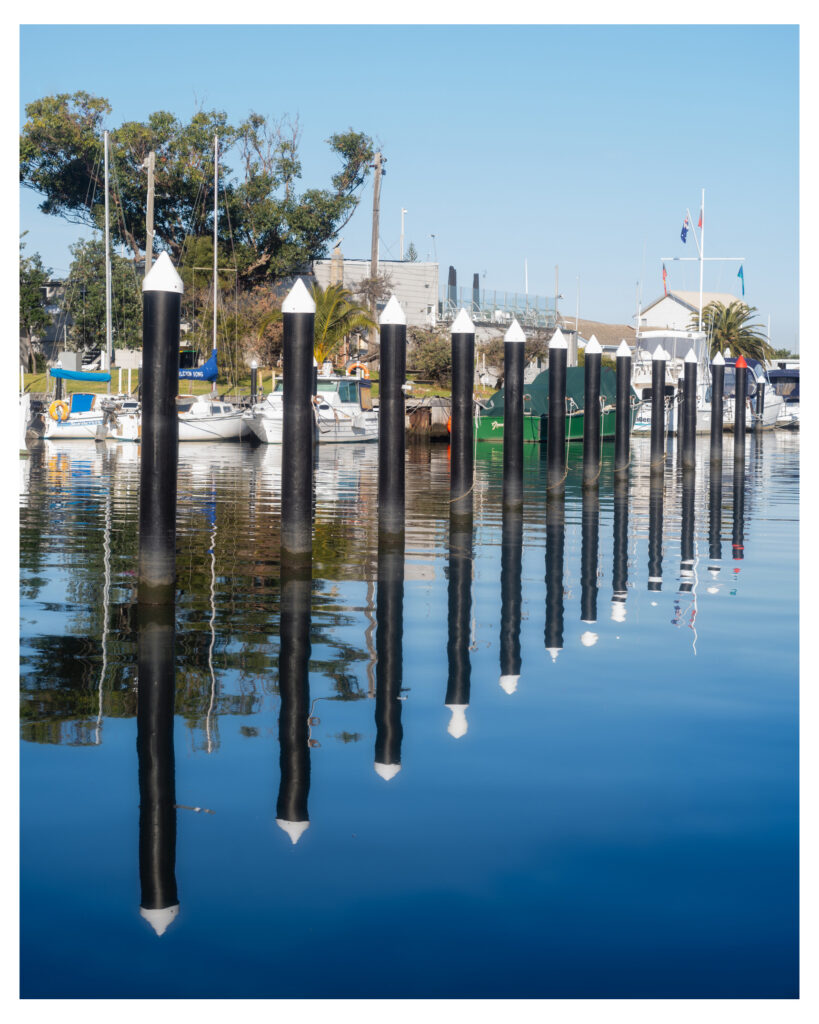

Sony A7RIV with HELIOS 44M-4 58mm F2 – 1/100th at F2.0 (note the bokeh shapes)

Sony A7RIV with HELIOS 44M-4 58mm F2 – 1/500th at F2.8 (note the swirly bokeh)

Admittedly, getting used to manual focus is a bit of a battle, but you can use your camera’s modern features to assist. Focus peaking and focus magnification will help immensely.

These featured helped manual focusing become surprisingly fast once I got into a rhythm. On static subjects or street scenes where I could anticipate motion, it felt meditative. Not having autofocus meant I had to see the shot before taking it—not chase it.

That said, low light was a bit trickier. Without stabilisation and with manual focus, I missed a few moments I normally would’ve nailed. Trying to get a sharp handheld shot wide open in fading light with no OSS meant a lot more ISO than usual or… accepting a little motion blur.

But here’s the surprise: I liked the constraints of using manual lenses. It made me more thoughtful, intentional, and selective.

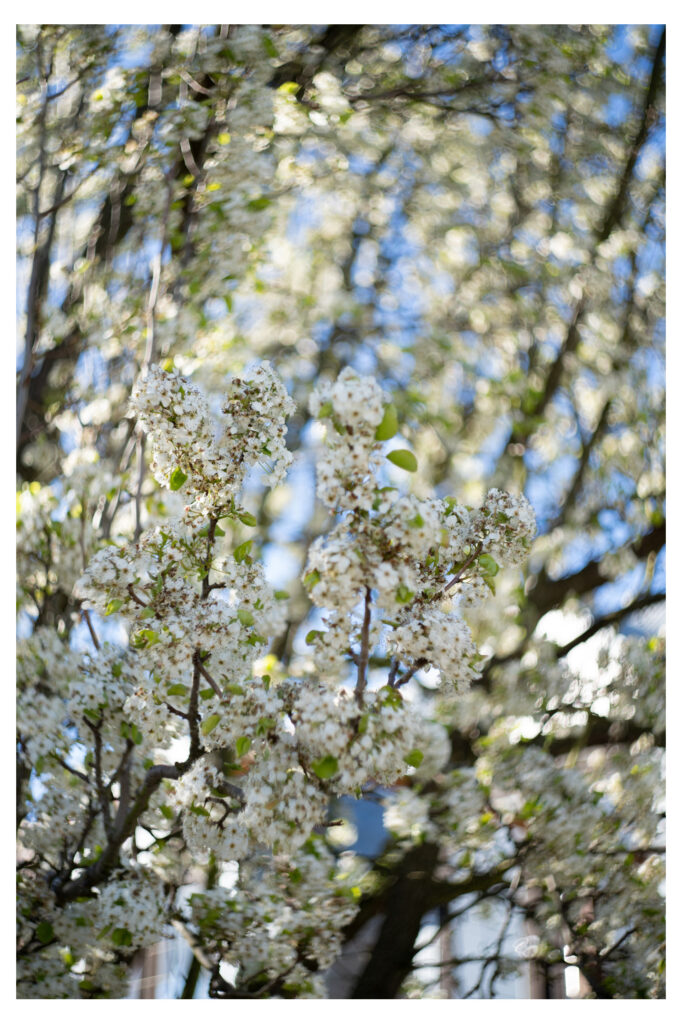

Suitability for Infrared Usage

Using vintage lenses for Infrared photography is worthy of its own post, however, in short, the problem with many modern lenses is that they exhibit what is known as a hotspot when used to capture images in the infrared spectrum.

Hotspots are mainly caused by light reflecting off antireflective lens coatings primarily designed for standard light wavelengths. Vintage lenses, with their simpler designs, tend to be less prone to this issue and as a result are favoured by many Infrared photographers.

All five of my vintage lenses performed nicely with no discernable hotspots.

Sony A7 (IR 720nm Converted) with SMC Takumar 24mm F3.5 – 1/40th at F8

Sony A7 (IR 720nm Converted) with SMC Takumar 24mm F3.5 – 1/320th at F5.6

Image/Output Quality

The images? Gorgeous. Sharp in the centre, a little soft and slightly dreamy around the edges (especially wide open). The colour rendering was slightly warm, with contrast that felt natural and analog. It had character, something modern glass sometimes sterilises in the quest for perfection.

Flare was definitely present when shooting into light sources, but rather than being a nuisance, it added a nostalgic glow that worked for most scenes. Chromatic aberration? A touch in high-contrast areas, but nothing Lightroom couldn’t tame.

Images probably wouldn’t win a lab test against modern glass, but in the field? They held their own—and produced images with their own distinct personality.

The Good – What I Liked About Vintage Lenses

- The feel: Manual focus and aperture rings are just satisfying to use.

- The process: Slowing down made me more thoughtful about composition and exposure.

- The price: You can get stunning vintage lenses for a fraction of what you’d pay for modern equivalents.

- The look: There’s a tangible difference in rendering and bokeh that adds depth and character to images.

The Bad – What I Didn’t Like So Much

- Autofocus: I missed it in fast-moving or low-light scenarios. There’s no getting around that.

- Image stabilisation: Would’ve helped in handheld street shots.

Would I Recommend Getting a Vintage Lens?

Absolutely. If you’re even remotely curious about the tactile experience of photography, or if you want to experiment with a look that breaks away from modern glass perfection, vintage manual lenses are 100% worth exploring.

It won’t replace your AF workhorse lenses. But it will rekindle a different kind of joy in the process, one click at a time.

So yes, I fully recommend trying out vintage all-manual lenses on your modern mirrorless camera. Just don’t be surprised if they end up becoming a permanent part of your kit.